Last Wednesday marked the 46th anniversary of the Great Northeast Blackout that darkened New York City overnight on November 9, 1965, 5:28pm

I was there. I graduated high school the year before and was working in the city at a graphics studio while attending Pratt Institute in Brooklyn three nights a week. What a different life I would have had if there had not been a war in Vietnam and a draft.

The power went out just about quitting time. The offices I worked in were on the 13th floor but they called it 14th. You know how that goes. I commuted 40 minutes into the city every day on what was then, the New York, New Haven & Hartford railroad. The trains ran on electricity so I had no plans to try to get home. A few co-workers lived uptown and decided to walk down the stairs and try to find a taxi home. That was the same thought that thousands of other office workers had so an hour or two later the men were back. Thankfully they brought sandwiches.

We had no lanterns or candles so being resourceful, we decided to try lighting the end of a grease pencil china marker. A few of those provided some light and as we later learned noxious fumes as well. I had only been doing photography for two years or so and the fact that I was able to get printable negatives of what was essentially, pure darkness, surprises me even today. The camera used was my first “good” camera; a Miranda F with 50mm f1.8 lens.

There was and has been much discussion after the event about “what we learned” and what could be done to prevent such a thing happening again. I am sure that systems and procedures were revised immediately after the failure that left 30 million people in the dark. In this computer age we have far more sophisticated systems in place to prevent such catastrophes. Yet there are more people and we all are more dependent on the services that electricity provides. With the capabilities of computers also come the vulnerabilities. The wars of the future will likely be fought on computer networks, not battlefields.

Hopefully today will be a better day at work than yesterday. Our DSL line was on and off all day.

David Bowie from the album “Heroes” – Blackout

Discipline and the Fifty

FOTOfusion recently wrapped up at the Palm Beach Photographic Centre. This annual event brings world class photographers to town to lecture and teach workshops. I had a chance to attend a few lectures including one by Ralph Gibson. The hour was spent surveying his work from beginning to present accompanied by comments on thought and process. I have always admired Gibson’s work and consider him one of the photographic masters of my generation. Unlike today’s digital photomontage masters or even Jerry Uelsmann with his multiple negative composites, Gibson manages to embody a surreal quality to his images merely by what he includes, or excludes from the frame. The brilliance of his mastery of this art became more evident to me after spending an hour with him. Little did I know that he started out as a street photographer! His street work predating the 1970 book, The Somnambulist, is inspired and his path to future work is evident.

Another thing I learned about Ralph Gibson is that like Henri Cartier-Bresson, he uses a Leica M series with a 50mm lens. Is there a magic to this focal length that these two, and other masters have discovered? As long as I have been a photographer the so called “normal” lens has been the one least used in many a photographer’s lens arsenal…unless it were a macro. Some pros don’t even own one. Most street photographers favor something wider: a 35mm or 28mm (or DX equivalent). The logic being that the photographer is part of the action rather than a distant observer. For today’s street shooters a 50mm lens carries somewhat of a stigma as producing images that are not really “street.” Worse, on a DX crop-sensor DSLR, the 50mm becomes a 75mm lens which is a short telephoto, totally unacceptable for street photography. Or does it?

The beauty of a 50mm lens is that it produces the same perspective as the human eye. Mount a fifty on a DSLR and look through the camera with both eyes open and the objects seen through both eyes are about the same size regardless of whether the camera is full frame or crop sensor. The spatial relationship of objects in the frame is the same regardless of the size of the camera’s sensor and approximates that of our natural vision. In order to qualify as a telephoto, a lens would compress those spatial relationships just like a wide angle lens expands them. Even on a DX camera body a 50mm is a “normal” lens, it’s just that the camera sensor is not big enough to accommodate the entire image the lens produces. That certainly does not make it a telephoto.

There is something to be said for discipline in our artistic endeavors. By not having to concern ourselves with process we can concentrate on the task at hand: the challenge our tools present us in expressing our vision. I remember a trip I took to Brazil some fifteen years ago. I did not want to risk taking my work cameras so I took an old camera body and several lenses ranging from 28mm to 200mm. I spent the whole trip changing lenses rather than trying to make photos through any one of them. Too many choices! Artists have always found ways of imposing limitations to challenge their artistic vision. Painters may select a certain canvas size or a limited color palette, or work with knives instead of brushes. Plastic cameras like the Diana are still popular and create a certain look through their limited capabilities. The photographic masters mentioned above and others I suspect, like Elliot Erwitt and Robert Frank, have discovered a certain magic in a 50mm normal lens and learned to respect the limitations of a singular way of seeing.

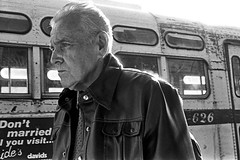

TOP: New York Minute, NYC 2011 – taken with 50mm f1.8

ABOVE: Ralph Gibson – West Palm Beach 2011

KC – DISCIPLINE