When I first began taking photographs it was pretty simple. I would see somebody or something interesting on the street and I would take a picture, The camera was loaded with Tri-X and had either a 24, 28 or 35mm lens on it. I didn’t know I was doing street photography and they weren’t even calling it that then. I had no intention of creating artistic images and any concept of style was founded on content. I don’t think that Winogrand, Freidlander, Arbus, Levitt, Erwitt or any of the pioneers of the genre ever thought about creating artistic photographs. In this new blossoming of street photography slick style is much admired.

In the first year of the SPNP project certain modern SP clichés became evident. We have the “people juxtaposed against advertising posters”, and “pocket of light”, many iterations of feet photography including “feet with colorful shoes against yellow road stripes”, pigeons are a recurring theme and reflections in windows are always a good way to fulfill any brief.

I stopped doing the SPNC briefs because I don’t want to be under pressure to have to take a certain picture. I want to shoot what I want to shoot. This past year a quote by Winogrand is sitting on my shoulder like a conscience; “How do you keep from taking the same pictures over and over again?” He went on to add, “When I go out to shoot I don’t have pictures in my head. I frame in terms of what I want to have in the picture.” That sounds deceptively simple. But he didn’t say “Look for dramatic light” or “Use diagonals and bold shapes.” Perhaps it is the absence of a consciously applied style that has made Winogrand’s work so enduring and monumental.

I have spent the past couple of years experimenting (with color!) and trying to see where I fit in between the content driven style of the past and the artsy style of the present. It has proven confusing. A few months ago I came up with the idea that maybe what Winogrand was getting at when he asked how we get around taking the same pictures all the time was at its point, an absence of style. In other words, people, their behavior and the world we live in is so infinitely variable that all we really need to do is decide what we want in the photographic frame and that when we apply certain ”style” we are in effect, making pictures that look like others.

Last year this photograph by OakT really captivated me and I continue to refer back to it. While seemingly simple in its presentation it resonates with humanity and carries the weight of daily existence we all face. It is more than just a photograph. It’s visual anthropology. I came across a quote by Joel Meyerowitz this week that is another arc in closing this whole circle of thought; “Over the years I have seen that photography is too often about the pictures only. To me it’s always been about ideas and the ideas that pictures generate.”

By Greg Allikas

Diane Arbus, Identical twins, Roselle, NJ 1966 (archives.evergreen.edu)

July 7 marked the sixth anniversary of John Szarkowski’s death and I thought it fitting to look at his contribution to photography, specifically how this single exhibition shaped what we now know as street photography.

Forty-six years ago the “New Documents” exhibition closed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The show featured ninety-four prints by three relatively unknown photographers; Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand. The exhibit was a landmark event for modern photography. The show, curated by John Szarkowski, the director of photography at the museum, inextricably linked the three photographers together and made their careers. The new student of photography should understand that at that time, except for the work of a handful of photographers, most museums did not have photography collections or departments. The photographs of Ansel Adams, Edward Steichen, Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston represent the type of work that did exist, if at all, in a museum. Few if any photography galleries existed. For the most part, photography was photography, not art. Because it was a mechanical process and perceived to be “easy” by most, easier than painting anyway, it was not taken seriously. One could argue that Szarkowski single-handedly changed that whole notion with this one exhibit. It took some time to take root, but “New Documents” set the movement in motion.

Szarkowksi succeeded Steichen at MOMA in 1962. He was only 37 and had a large pair of shoes to fill. Stiechen had curated the monumental “Family of Man” exhibition in 1955. It contained 500 images by 273 photographers both famous and unknown and was built on a theme of the human experience…birth, death, love, joy, sorrow. The show was a huge success and toured the world. The book is still popular. While “Family of Man” was a landmark exhibition it did not break any new ground in the photographic vocabulary and relied on existing documentary traditions. It was more about the subjects of the photographs than the photographs themselves. Photojournalism was socially responsible and served to report, inform and affect change. Arbus, Friedlander and Winogrand had no such goals. They selfishly photographed for themselves. Szarkowski wrote in his introduction to “New Documents”1, “In the past decade this new generation of photographers has redirected the technique and aesthetic of documentary photography to more personal ends. Their aim has been not to reform life but to know it, not to persuade but to understand. The world, in spite of its terrors, is approached as the ultimate source of wonder and fascination, no less precious for being irrational and incoherent.” His egalitarian view that anyone, anywhere, anytime could create a great photograph worthy of comparison to the masters shaped the future of photography and has become commonplace within the photo sharing websites of today’s digital age, where stars are born and die every day.

1967 was the year of the “summer of love” yet it was a turbulent year in America. The country was deeply involved in Vietnam and civil disobedience plagued cities across the country. Riots in Detroit required the National Guard to restore order and left dozens of people dead. The Equal Rights Amendment would not be passed for another five years. Cameras used film and photographers had darkrooms. With so many social and political events ripe for documentary photography, 1967 seemed an inauspicious year to present an exhibit of photographers so preoccupied with their own personal agendas.

Lee Friedlander, New York City 1965 (sfmoma.org)

“New Documents” received a cool reception. Jacob Deschin wrote, “”The observations of the photographers are noted as oddities in personality, situation, incident, movement, and the vagaries of chance,” in his New York Times review2. Nine years later Szarkowski would take an even bolder risk with “William Eggleston’s Guide,” which was met with even more skepticism. Today Eggleston is considered to have set the stage for fine art color photography3 at a time when the materials and medium were far more limited than they are today.

What did Arbus, Freidland and Winogrand have in common other than working in black and white? They all used small 35mm cameras, although Arbus eventually moved up to a 2-¼ square Rolleiflex. The photographs of the two men are closer to each other than the work of Arbus is to either of them, Both men realized the importance of photographic context, but Friedlander was inclined to often deal only with the elements of place while Winogrand was self-admittedly interested in people. While Arbus may have taken photos on the street, she was primarily a portraitist and is lumped into the street photography genre solely because of her inclusion in “New Documents.” Her methodology had little to do with the “catch as catch can” approach of Friedlander and Winogrand and depended on cultivating a trust with her subjects, sometimes over a period of time. Perhaps Szarkowski sums it up best in this excerpt from a museum press release4 for the exhibit, “What unites these three photographers is not style or sensibility; each has a distinct and personal sense of the use of photography and the meanings of the world. What is held in common is the belief that the world is worth looking at, and the courage to look at it without theorizing.”

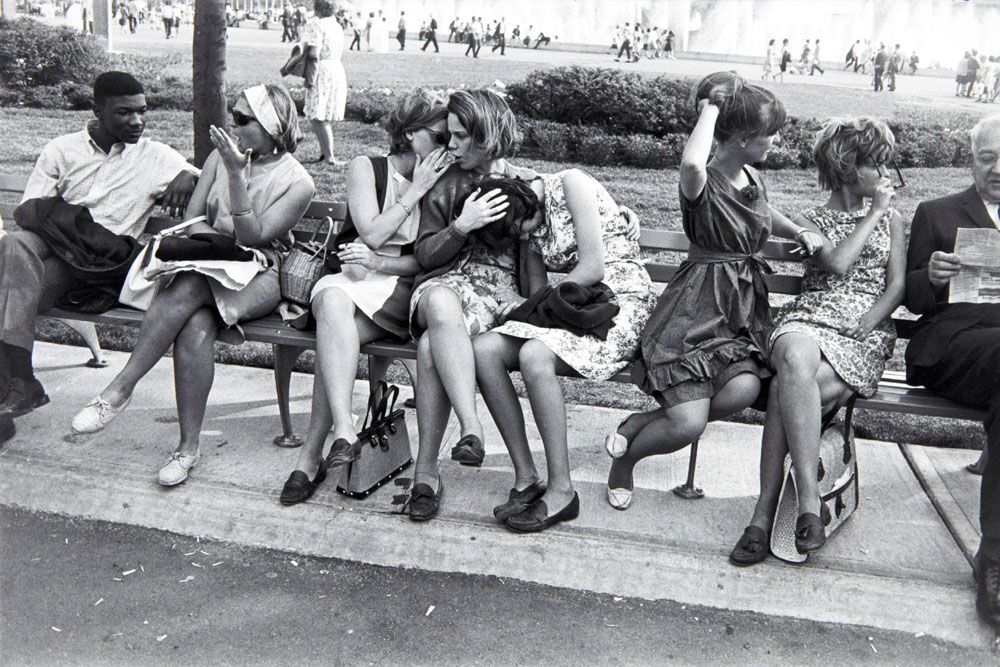

Garry Winogrand, World’s Fair 1964 (masters-of-photography.com)

In 1967 street photography was not a new invention. One could argue that the early work of Atget, Brassai and Kertesz was essentially “street photography”, although Brassai posed his subjects on occasion. And of course there were Henri Cartier-Bresson, Helen Levitt and Lisette Model (whom Arbus studied under) and Robert Frank’s opus from ten years earlier, The Americans,. Winogrand himself was profoundly influenced by Walker Evans, American Photographs. These works, however, relied more heavily on documentary traditions than the frivolity of Friedlander’s storefront reflections or Winogrand’s public relations. In an interview with John Pilson5 published in 2011 Tod Papageorge describes Sunday night get-togethers (including Joel Meyrowitz) at Garry Winogrand’s house as being focused on discovering just what photography was, and wasn’t. Papageorge goes on to say that much of the conversation was about photographic “problems” and strategies to solve them. How much information could be crammed on to a 24x36mm piece of film and still be coherent when viewed as a print? Must the horizon be level? What happens when you use flash? What happens when you use flash at a slow shutter speed? What happens to something when you photograph it? In an essay for the catalog for the exhibit, “The Social Scene”6, A.D. Coleman writes about “New Documents”, “Increasingly asymmetrical, unbalanced, fragmented, even messy, especially in contrast to preceding photography, this work demanded of both photographer and viewer an openness to radically unconventional formal structures.” With its snapshot view of the world, the work carried an authenticity that was not evident in the work of say, Eugene Smith, or the FSA photographers where it could be said that the photographs were not entirely candid, or entirely honest. Many of the visual mannerisms we now take for granted had not been seen before “New Documents” nor had such seemingly banal subject matter. The ways in which these three photographers used their cameras opened up a new visual vocabulary for generations of photographers. But it was John Szarkowski’s willingness to take risks that expanded the borders of modern photography. It may be no idle claim that he was once referred to as “the man who taught America how to look at photographs.”

Here is a list of the photographs that appeared in the exhibit.

Notes

1. Museum of Modern Art archives; press release, February 28, 1967;www.moma.org

2. The New York Times; July 9, 2007; www.nytimes.com

3. While color photography was commonplace by the 1960’s it was nothing compared to today’s technologies. Kodachrome was very sharp film but involved a proprietary process that only few color labs could afford. Hence, film had to be sent off for processing. At ASA 25 it was very slow and full sun would give an exposure of about f5.6 @ 250. C-41 color negative films were also slow but gave one additional f-stop at ASA 64. The various Ektachrome films were not nearly as fine grained as Kodachrome and the dyes in processed slides were not as stable as Kodachrome either. If not stored properly you could expect to find faded colors and fungus on old Ektachromes. We referred to High Speed Ektachrome of the 70’s (ASA 160) as having “grain the size of golfballs.”The biggest obstacle however for color to be used for so called “fine art” photography was the available processes for making prints. Conventional “C prints” of the time made from color negatives (or internegatives from slides) had dyes that were extremely fugitive. If displayed prints received significant light, natural or artificial, fading could be noticed in as little as a few years. Who wants a piece of art that needs to be kept in a closet? Also, color was never truly faithful even if printed by a professional lab. Dye transfer prints were the best color print available at the time and were relatively stable, but they were costly and only available from top tier professional photo labs. Cibachrome prints came later. While permanent, color fidelity was hit or miss and the process used toxic chemicals hazardous to home users. Consequently, most serious photographers who sought a place in “fine art” photography worked in black and white. Properly processed and stored silver gelatin prints should have an unlimited life.

4. Museum of Modern Art archives; press release, February 28, 1967;www.moma.org

5. John Pilson; “Taking Pictures”, Tod Papageorge in Conversation with John Pilson”; Aperture #204, Fall 2011; New York

6. A.D. Coleman; “The Social Scene”, The Ralph M. Parsons Foundation Photography Collection at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Los Angeles;2000

FOTOfusion recently wrapped up at the Palm Beach Photographic Centre. This annual event brings world class photographers to town to lecture and teach workshops. I had a chance to attend a few lectures including one by Ralph Gibson. The hour was spent surveying his work from beginning to present accompanied by comments on thought and process. I have always admired Gibson’s work and consider him one of the photographic masters of my generation. Unlike today’s digital photomontage masters or even Jerry Uelsmann with his multiple negative composites, Gibson manages to embody a surreal quality to his images merely by what he includes, or excludes from the frame. The brilliance of his mastery of this art became more evident to me after spending an hour with him. Little did I know that he started out as a street photographer! His street work predating the 1970 book, The Somnambulist, is inspired and his path to future work is evident.

Another thing I learned about Ralph Gibson is that like Henri Cartier-Bresson, he uses a Leica M series with a 50mm lens. Is there a magic to this focal length that these two, and other masters have discovered? As long as I have been a photographer the so called “normal” lens has been the one least used in many a photographer’s lens arsenal…unless it were a macro. Some pros don’t even own one. Most street photographers favor something wider: a 35mm or 28mm (or DX equivalent). The logic being that the photographer is part of the action rather than a distant observer. For today’s street shooters a 50mm lens carries somewhat of a stigma as producing images that are not really “street.” Worse, on a DX crop-sensor DSLR, the 50mm becomes a 75mm lens which is a short telephoto, totally unacceptable for street photography. Or does it?

The beauty of a 50mm lens is that it produces the same perspective as the human eye. Mount a fifty on a DSLR and look through the camera with both eyes open and the objects seen through both eyes are about the same size regardless of whether the camera is full frame or crop sensor. The spatial relationship of objects in the frame is the same regardless of the size of the camera’s sensor and approximates that of our natural vision. In order to qualify as a telephoto, a lens would compress those spatial relationships just like a wide angle lens expands them. Even on a DX camera body a 50mm is a “normal” lens, it’s just that the camera sensor is not big enough to accommodate the entire image the lens produces. That certainly does not make it a telephoto.

There is something to be said for discipline in our artistic endeavors. By not having to concern ourselves with process we can concentrate on the task at hand: the challenge our tools present us in expressing our vision. I remember a trip I took to Brazil some fifteen years ago. I did not want to risk taking my work cameras so I took an old camera body and several lenses ranging from 28mm to 200mm. I spent the whole trip changing lenses rather than trying to make photos through any one of them. Too many choices! Artists have always found ways of imposing limitations to challenge their artistic vision. Painters may select a certain canvas size or a limited color palette, or work with knives instead of brushes. Plastic cameras like the Diana are still popular and create a certain look through their limited capabilities. The photographic masters mentioned above and others I suspect, like Elliot Erwitt and Robert Frank, have discovered a certain magic in a 50mm normal lens and learned to respect the limitations of a singular way of seeing.

TOP: New York Minute, NYC 2011 – taken with 50mm f1.8

ABOVE: Ralph Gibson – West Palm Beach 2011

KC - DISCIPLINE

Last Wednesday marked the 46th anniversary of the Great Northeast Blackout that darkened New York City overnight on November 9, 1965, 5:28pm

I was there. I graduated high school the year before and was working in the city at a graphics studio while attending Pratt Institute in Brooklyn three nights a week. What a different life I would have had if there had not been a war in Vietnam and a draft.

The power went out just about quitting time. The offices I worked in were on the 13th floor but they called it 14th. You know how that goes. I commuted 40 minutes into the city every day on what was then, the New York, New Haven & Hartford railroad. The trains ran on electricity so I had no plans to try to get home. A few co-workers lived uptown and decided to walk down the stairs and try to find a taxi home. That was the same thought that thousands of other office workers had so an hour or two later the men were back. Thankfully they brought sandwiches.

We had no lanterns or candles so being resourceful, we decided to try lighting the end of a grease pencil china marker. A few of those provided some light and as we later learned noxious fumes as well. I had only been doing photography for two years or so and the fact that I was able to get printable negatives of what was essentially, pure darkness, surprises me even today. The camera used was my first “good” camera; a Miranda F with 50mm f1.8 lens.

There was and has been much discussion after the event about “what we learned” and what could be done to prevent such a thing happening again. I am sure that systems and procedures were revised immediately after the failure that left 30 million people in the dark. In this computer age we have far more sophisticated systems in place to prevent such catastrophes. Yet there are more people and we all are more dependent on the services that electricity provides. With the capabilities of computers also come the vulnerabilities. The wars of the future will likely be fought on computer networks, not battlefields.

Hopefully today will be a better day at work than yesterday. Our DSL line was on and off all day.

David Bowie from the album “Heroes” - Blackout

Hold the edit!

A few posts earlier, I posted a comment by Garry Winogrand about saving your contact sheets for a year before looking at them. His reason was to separate the act of taking the photographs from the photographs themselves. This really makes a good bit of sense and I personally find that I have a hard time selecting images from a recently shot set, especially street photography.

Going back through an archive can often yield overlooked gems. The older the better? Street photos naturally aquire a patina with age…call it retro if you like. Naturally, because they depict a time gone by.

In 1974 after selling our photo studio, Valbuena and I went separate ways. I went north. That summer I packed most of my belongings into my 1967 red Volvo and like Lincoln Duncan, headed down the turnpike for New England. I took my time and as many backroads as I could find. There ain’t much to photograph along the interstate! After heading north through western Georgia I found myself in the curious copper mining berg of Ducktown. It seemed to me then a strange place, perhaps because of the mining activities at the time.

A few weeks ago I came across this shot while looking through some boxes of contact sheets and negs for a specific photo. Somehow I had missed it 35 years ago. It had never been printed nor was the contact sheet marked for printing it. Today, I really like the image. The hat and the cigar make it, but he is also nicely joined to the lightpost by his shadow. I like the minimalist building which may be a post office, but I don’t recall. The final bit of humor that appeals to me is the exiting man with his bowed head. What else does one do in Ducktown but “duck”?

A year or two ago I had a section on my website of tattoos that people had sent photos of. All were done using images from the Orchid Photo Page as reference. One of the best examples of tattoo art is pictured here. Fortunately she lived in South Florida and even more fortunately, was willing to participate in a recreation of Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’ famous Odalisque. Ingres was one of my early heroes from art school days so it was especially rewarding to create the photo…with a modern twist! The photo was taken two years ago.

Looking at Ingres’ painting today, it has the look of Audobon’s birds: something about the anatomy seems askew.

L to R: Winogrand, ?, Jill Grossman, Me, Bill Cottman, Mike Pretzer, Peter Gold

In 1973 I was fortunate enough to take a week-long workshop with Garry Winogrand. It was at the Country Photography Workshop in Woodman, Wisconsin. His point of view of what a photograph actually is, is bizarre, yet infinitely true. Light on surface. Period. We would go out shooting to the small towns in central Wisconsin, Prarie Du Chien, Dodgeville, Lancaster…come back and process our film and make prints, then critique the work after a family style country dinner. It was a great period of growth for me and the train ride there and back was an adventure in itself. When he died in 1984 Winogrand left behind thousands of rolls of undeveloped film, and thousands of unedited contact sheets. This 1982 interview with Bill Moyer offers some insight into the personality of the photographer and his views on what photography is and is not.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tl4f-QFCUek&hl=en&fs=1&]

Can the Camera Shape the Photographer?

A conversation with Mike Aviña, Chris Farling, David Horton, Hector Isaac and Tom Young

A recent magazine ad for the Fujifilm X-T1 said, “The camera you carry is as important as the images you make.” But among street photographers, it is not cool to obsessively discuss “gear.” We take that for granted - cameras are just tools. While that is true, there is no better tonic for “photographers’ block” than a new camera or lens. Some photographers have truly found their vision when they switched to a certain camera. Back in the pre-digital days you had a camera. It was either a Leica, or an SLR. And you kept it forever. Today with so many choices of equipment, a photographer can pretty much find the perfect camera to suit their shooting style and personality. Or is it the other way around? In this post we hope to discover how the equipment a street photographer uses influences what their pictures look like.

GA

Chris, you were shooting with an Olympus E-P1. Your work was solid and gaining some notice. Then you bought an OM-D E-M5 in the spring of 2012 and it seems like your vision really blossomed. I immediately noticed the quality of your work ramp up several notches and that trend continues. Do you feel that you held a vision that the OM-D finally released? Or did the new equipment present possibilities the E-P1 didn’t… i.e., eye-level viewing, fast autofocus, etc.

Chris Farling (CF)

I don’t want to diss the E-P1 overmuch in that the E-P1 itself was a quantum leap over the fully automatic mode-style shooting of the digital point-and-shoots that I had owned over the previous decade. When I committed to ponying up the $$$ to buy the E-P1, I made a parallel commitment to being more serious in my study and practice of photography. It was with the E-P1 that I really dug into controlling aperture and shutter speed and exploring different focal lengths and lenses. I’m actually glad I started with a camera that had some clear limitations (no VF, iffy sensor, slow AF, & poor high-ISO), much the way you need to play the $&@! out of a student horn before moving onto a more powerful but perhaps more complicated or less forgiving instrument in music. Everyone starting out wants to buy some perfect camera that will make them a brilliant photographer overnight, but the paradox is that it’s only through working around limitations that you grow and develop good habits. If you start out with everything handed to you, it can breed in you a certain laziness and you’ll most likely get bored and frustrated.

The E-P1 was also my first experience using fixed prime lenses and that more than anything helped me to “see” as a street photographer would and to be able to pre-visualize frames to some degree. It was really a wonderful camera to experiment with and learn on and I don’t think I will ever sell it.

GA

So you’re saying that a more basic camera can provide a better learning experience?

CF

Exactly. It really did liberate me when I upgraded to the E-M5 along with the Oly 12mm f2 lens because I had much of the basics in place from the E-P1. Most of the gains weren’t surprising in that I knew what I wanted out of this new camera and what advantages it held over the old one. I honestly can’t imagine needing a more powerful camera in the foreseeable future.

GA

That was a pretty wide lens to start with! Just what are those advantages the E-M5 gives you?

CF

The one thing that I want from a camera more than anything else is versatility. And I include the lightweight form factor of the m4/3 system as a key part of that versatility. Not for me the heavy necklace of an SLR… I like to be able to shoot quickly and reflexively and so I don’t even want the camera to be on a strap. The E-M5’s EVF was a real boon to helping me execute better edge-to-edge compositions. I for one really like having all the settings info available in the EVF, though I know many prefer optical ones. The touchscreen, which allows you to tap a focal point or even to release the shutter directly, added even more flexibility. The almost instantaneous AF (as well as the simple zone focusing capability of the 12mm lens’s pull ring) meant that I could depend on my own sense of timing and reflexes and not worry that the camera wouldn’t respond when I was ready. The E-M5 helped me to learn more about on- and off-camera flash. Perhaps the most useful thing, surprisingly enough, was simply the extra customizable dial and button, allowing me to have immediate tactile access to virtually any setting I would want to change quickly in anticipation of the next shot. Also, it bears mentioning that the rich Olympus JPG quality from both cameras has influenced my color sensibility.

As much as I like the E-M5 and feel that it has helped me develop and execute my vision, I’ve since adopted the APS-C sensor Ricoh GR as my principal camera, reserving the E-M5 for special situations where I want the different lenses or the weatherproofing. In many ways, the Ricoh is a step backwards in quality and features, yet it is so perfectly portable and well-designed in its flexibility (a real photographer’s camera) that those advantages trump all other considerations. Plus there’s that awesome TAv mode that let’s you specify both aperture AND shutter speed… I find the Ricoh is the perfect camera for my style of quick close-in shooting with a fixed 28mm-equiv. and I suffer little when adapting it to other types of shooting.

Click for a gallery of images by Chris Farling

GA

So with the E-M5 you became accustomed to the convenience of customizable dials? That would make the GR a logical move because, since the line’s inception, it has been praised for its flexible interface. As DP Review said, “We’ve often referred to the Ricoh interface as arguably the best enthusiast-focused interface on a compact camera.”

David, you followed a similar path as Chris, moving from an E-P2 up to the OM-D E-M5. Among this group of photographers, you used the focal length closest to what is considered a “normal” lens: 20mm (40mm equivalent). There is less margin for framing errors than with a 28mm or even 35mm. As a graphic designer, tell us how the precise eye-level framing of the OM-D has influenced your photography, especially with the 20mm lens.

David Horton (DH)

When I first started dabbling in SP, I was using a Canon G9 which has a 35mm default lens. I liked that length a lot. When I moved to the E-P2, I opted for the Panasonic 20mm (40mm equiv.) because it was considerably faster than the 17mm Oly lens* (34mm equiv.) and it received considerably better ratings and reviews.

GA

*You mean the Olympus 17mm f2.8 Pancake, correct?

DH

Yes. Oly’s first 17mm prime did not have very good performance especially in the corners. Although I used the Pany 20mm almost exclusively for over a year (and was very pleased with the IQ of the lens), I often found the focal length limiting. I wished it was a little wider.

The primary reason I moved to the EM-5 was speed. Although I adapted to the slow autofocus of the E-P2, I was missing more and more shots. Although the add-on EVF on the E-P2 was acceptable, it was a bit cumbersome. I shoot exclusively through a viewfinder. So the ergonomic design of the built-in viewfinder on the EM5 was also very appealing. What I didn’t know until I received the camera is that, to benefit from the increased speed of the EM-5, you also had to have one of the newer Oly lenses. At the time I bought I camera, the fast Oly lenses only existed in 12mm and 45mm lenses. The 12mm (24mm equiv.) was too wide for me. I waited for at least three months for the rumored 17mm 1.8 lens to come out. (It was my dream lens.) I preordered it and got it as soon as it released. I’ve used it exclusively since the day I got it. The combination of the EM-5 and that lens is extremely fast.

The other thing I like about the EM-5 as opposed to something like the Fuji X100 (which I also considered) is the ability to change lenses. Although I rarely do, it’s nice to have that option. I always carry the 45mm 1.8 Oly lens (90m equiv.) with me too, just in case.

Click for a gallery of images by David Horton

GA

It is nice to have the ability to change lenses, particularly when on a trip, even if you don’t do it often.

Mike, you have used quite a variety of equipment, from Leica M3 to Sony RX1 and many things in between including compact P&S’s and the Ricoh GR. I know that you are a dedicated student of photography with a deep curiosity about what is possible. Does this explain your variety of equipment? You seem to always come back to shooting b&w and I have the impression that, ideally, film is your medium of choice and because of that much of your digital work looks like film.

Mike Aviña (MA)

I’d like to challenge the conventional wisdom of sticking to one camera and one lens. There is a time and a place for sticking to a narrow set of gear. When you get completely accustomed to one focal length and one camera the gear does become more intuitive, you can set up shots and frame them before you pull the camera up to your face because you know where to stand at what distance to include given elements. That said, smaller cameras have certain advantages: deep depth of field, very fast autofocus, and tilt-screens. There are world-class photographers that have discovered and exploited these advantages. I just purchased a published book shot entirely by phone-the images are superlative. I’ve made 12” by 16” prints from an LX7-they look great.

To answer your first question-yes, I prefer film. The dynamic range of film and the separation of subjects one can achieve with shallow depth of field on a fast lens is a necessary creative tool. I have never used complicated post-processing to add blur to digital images; this is a method that ends up looking artificial. A wide, fast lens on either a full-frame sensor or over film is therefore a must-have. Shallow depth of field however is only one tool and not one I use all or even most of the time.

GA

Arguably, you can come pretty close having a digital image file look like it was shot with film in post processing. But the methodology of shooting film is a whole ‘nother animal.

MA

Film versus digital ia probably better left for another discussion! I also have an abiding love for small, pocketable, point-and-shoot cameras. As others have mentioned above, small cameras are easier to haul all day. In addition, shooting like a tourist, with innocuous little shots framed through the LCD rather than a viewfinder, is often more effective than pulling a big rig up to your face and clacking away. Even with a small rangefinder, people react more when you pull a camera up to your face than they do to an apparent tourist snapping casually with the LCD. I tend to frame faces off center; when using a wide angle lens this means people are often not sure they are in the shot because it isn’t clear you are shooting at them. The shooter and the subject have a complicit agreement to the fiction-the photographer is shooting something else; the subject ignores the shooter as long as it isn’t too intrusive. This helps one work close in crowded spaces. Having a bundle of different tools allows flexibility and simultaneous exploration of different creative options.

GA

You make a very good point Mike. Why shouldn’t we use whatever tool best suits the situation? Some of our peers carry dslr’s with a zoom lens mounted that will cover most scenes. Maybe one of them will comment to the pros and cons of a zoom.

Interesting path you have followed Chris… from LCD framing, to eye-level framing, back to LCD framing. I found myself “borrowing” the small Samsung EX2F I bought for my wife and became addicted to the tilt screen. I find that I am very comfortable shooting from waist level and I really prefer the perspective of that PoV, rather than “looking down” at everything from my 6’2″ eye level.

How hard was it to adjust back to the loose framing of the GR’s LCD screen versus the precise eye-level framing of the E-M5? The concrete canyons of NY offer some shade to better see the screen, but how do you frame in bright sunlight when you travel? How often do you use the optical viewfinder?

CF

I do use the optical viewfinder on the GR sometimes (in a way, it’s less obtrusive and noticeable than holding the camera out from your body) but I have a tougher time seeing all four edges of the frame in the viewfinder than I do with the screen. As wide as I generally shoot, I have to kind of scroll with my eye in each direction and that’s too limiting and slow for me. I also don’t like the tunnel vision that develops where you can’t receive new information about the way the scene is changing and what’s happening on the margins with your peripheral vision. With the OVF, you also don’t see the central AF point if you’re using that to lock AF and then recompose. It may seem like a minor point, but I’m also very left-eye dominant so I have to block my whole face with the camera when using the VF, even if it was a corner-mounted one.

GA

An interesting observation I have made is how most of us frame on an LCD using both eyes, but frame through an eye level viewfinder with one eye closed. Truth be told, for street photography, framing using any device is probably best done with both eyes open, but a hard habit to get into with an eye level viewfinder. I find an optical viewfinder more conducive to shooting with both eyes open and it gives you the advantage of seeing what is going on outside of, and about to enter or leave the frame.

CF

That is an interesting point about shooting with both eyes open. That may be what I like about using the LCD of the GR. Viewing the LCD in sunlight hasn’t bothered me too much with either the E-M5 or the GRD since the screens can be made pretty bright. Most of the time your own body acts as shade and, even when it doesn’t, you can still easily see which shapes and areas of light and dark correspond to what you’re seeing with the naked eye. I think it’s actually kind of cool having a slight degree of abstraction (less detail) when considering the composition, the same way a photo thumbnail is often easier to use for judging the effectiveness of a composition in editing than the enlarged version.

It’s also interesting that you say you prefer shooting from a more mid-body angle than always looking down at everything. Being 6’2’’, I have the same issue and, while using the 12mm lens almost exclusively for a year, I became cognizant of the great care one must take in controlling the perspective distortion with a wide-angle lens. Even having backed off to the 28-mm equiv. of the Ricoh, I still think that the default orientation with such a lens should be relatively straight on and not tilted excessively.

DH

My biggest gripe with the EM-5 is you have to rely too heavily on the digital interface. I wish there were manual knobs to adjust the ISO, aperture, and shutter speed. Since I don’t use the LCD, I have it turned off. To adjust any of these settings, I either have to hold the camera to my eye and turn the knobs or turn the LCD on and adjust them. Neither option is ideal or fast enough. This is what I find so appealing about the X100 or a Leica. I also can’t wait until they design better battery life for these digital cameras. As Chris can tell you (from spending a day shooting with me), I opt to carry a number of batteries with me than worry about preserving battery life in the camera. I turn it on and leave it on. When I need to react quickly, I don’t want to have to wonder if the screen’s going to be black when I bring it to my eye.

GA

That’s what evolution has brought to cameras, David. With a basic film camera, like an M3 or Nikon F you have two settings: shutter speed and aperture… and, of course, focus (and film choice). Cramming so many features into a small digital camera leads to compromises.

Mike made a good point about not limiting ourselves to a single tool. Sometimes we tend to set unnecessary limitations for ourselves. Although we may at any given time favor a particular set of gear, I think most of us here have more than a single camera. We always have the option to change cameras if a project or different direction comes to us Having your equipment be intuitive is the most compelling reason for limiting equipment choices. When I saw you this last summer Mike, you were using the Sony RX1. The IQ is the obvious reason why this camera has a strong following. Is it your perfect camera? If not, what would be? The others can answer this as well.

MA

The M3 is, for me, more or less the perfect camera-I am just reluctant to keep spending the money on film. The chemicals also concern me. For an everyday digital shooter the Ricoh GR may be my favorite. The RX1 has laggy autofocus which hinders the advantage of the high IQ and beautiful rendering that the Zeiss lens offers.

Click for a gallery of images by Mike Aviña

GA

David, you mention that you use an eye level viewfinder exclusively-is that because you want precise framing? How come you didn’t gravitate toward a DSLR? There are plenty of choices in size and features to fit any budget and many SP’ers use them. Was it because you already had m4/3 glass?

DH

I certainly find my framing more precise and that’s certainly one of the primary reasons I shoot this way. Perhaps, the more significant reason is that I feel “more at one” with the camera and the subject(s). I shoot a lot of portraiture and even when I’m not shooting conventional portraiture, it’s very important that I’m in sync and “connected” with my subjects. Facial expressions and details are very important to me; these are impossible for me to see if I’m relying on a screen. Shooting with a screen is fine for shapes and loose compositions but it’s not very precise—certainly not precise enough for me.

The reason I’m not interested in a DSLR is size. I don’t like to draw attention to the camera and a DSLR certainly does that. I’m also not interested in lugging one of those suckers around the city on a regular basis. I will occasionally lust after the IQ of DSLR sensors but the trade off is not worth it to me. I’ve spent the day shooting with friends that use DSLRs and after a day walking 10 miles around a city, they are not happy campers. The smaller and lighter the camera, the more likely you are to bring it with you.

GA

Tom, you use a full-frame DSLR. While the 5D is not huge by DSLR standards, it is huge in terms of what everyone else here uses. Obviously it’s hard to be inconspicuous. How do you work around that? I would assume that the quality and precise framing a DSLR offers is important to the type of pictures you want to create.

Tom Young (TY)

There’s a number of different reasons I shoot with an SLR. For one thing, I don’t only shoot street. I also do weddings, events, the odd corporate photography gig. I even shoot landscapes! Egad! So while the 5D is a big rig, for many of the situations I find myself using my camera its size doesn’t really matter, and its image quality is definitely a plus.

But for my street work it can also be an asset. I shoot in a town that is really dark in the winter. During the darkest months, the sun doesn’t get up until after I get to my day job, and is already down again before I leave. And I dabble a bit with flash, but available light is generally my preference. I love the night, really, the strong contrast, dramatic brightness surrounded by black. The full-frame SLR lets me work in that environment and still get nice clean shots.

GA

I would imagine the high ISO image quality to be a must in the arctic. But how do you deal with subjects when they see you pointing that big honker at them?

TY

Hey wait a minute, Edmonton may be north, but it’s not the artic!!! I find that the right attitude is the key to remaining inconspicuous. People may be more likely to notice my camera because it’s big, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they will care what I’m doing with it. When I first started shooting street, it seemed that people noticed me more than they do now, probably because I spent a lot of time sweating bullets about what I was doing. I really didn’t want to be noticed. And I assumed people would think it was odd. I hadn’t squared in my own head what my motive was. I knew what types of images I wanted to produce, but I didn’t have a clear sense of purpose. Best way to stand out in a crowd? Look embarrassed or uncomfortable while wielding a big camera, or worse, a small camera.

Click for a gallery of images by Tom Young

GA

That is excellent advice Tom.

TY

With experience, that fear has dropped way off for me. Now, when I pull out my camera, I’m pretty confident about what I’m doing. And while the odd person may raise an eyebrow, most people don’t seem to think anything is unusual about what I’m up to. I can only assume that means that I look like I belong in the landscape now. Hidden in plain sight, in a sense, despite the fact that I don’t really try to hide my activities any more. So I think the knock against SLRs being too big for street work is a little overblown.

Mind you, it probably helps that I’m not a terribly in-your-face shooter. If I was shooting Gilden-style, the big camera might tip people off before I could get close enough…

GA

A lot of photographers feel that anything longer than 50mm equiv, or even 35mm, is “against the rules” for street photography. How do any of you feel about that David? You sometimes use the Olympus 45mm f1.8 (90mm equivalent).

DH

I think many “rules” of street photography are pretty ridiculous. I try not to pay a lot of attention to the rules. I believe all that really matters is the success of the shot. Yes, there is an energy and authenticity that comes from a wider lens that is very appropriate for the street—there’s good reason most of us use them most of the time. But limiting yourself to that perspective exclusively is a bit short-sighted (sorry, couldn’t help myself). A lot of magic can happen when compressing images. It can be a very painterly way of seeing, especially with a large aperture. You paint with colors and shapes rather than objects or subjects. It’s a slower, more studied way of seeing. Saul Leiter is a perfect example of this. It all depends on the mood you’re trying to achieve, the story you’re trying to tell.

GA

You shoot with a Fuji x100, Hector. Am I correct in understanding this is your first camera? You don’t have previous experience with film? The x100 is a popular camera with street photographers. You mentioned that it took awhile for you to feel comfortable with it. I have heard other reports that there was a steep learning curve with this camera. How does the hybrid viewfinder help or limit your shooting style? Is a fixed focal length limiting… do you ever wish it was a little wider, or longer?

Hector Issac (HI)

You are correct, Greg, I had no previous experience with film or any other medium and the Fujifilm x100 was my first camera. Recently, I was asked by a friend… Why that camera? I didn’t have an answer. I still don’t, but I’m glad I got it.

For most of those coming with a broader photographic background, the x100 was a struggle, for me it was a love/hate situation that still exists. After my first try, I almost sold it, then it was left on the shelf for one or two months. It took me about another three to four months to get comfortable enough to get what I wanted. The main issue back then (cough cough) was the autofocus, well … it sucked, so I decided to learn to work manually and zone focus, rather than sell the camera and buy another… Best decision I ever made.

I’m a bit obsessive when I’m interesting in learning something, so my learning curve was rather steep given the amount of time I spent to learn my camera and about photography in general. The hybrid viewfinder helped me learn the camera’s frame lines, even if the lag was a problem.

GA

Thanks Hector. I have heard from others that the x100 has a steep learning curve. But those who master it love it to the point of becoming evangelists. Interesting choice as a first camera but it seems that diving in on the deep end and making the commitment has served you well!

There are many ways a photographer’s equipment choices shape the pictures they produce. Even though the street photography genre has been slow to embrace anything other than straight, unmanipulated images, today we have so many more choices in equipment and post processing than we did on the pre-digital era. While it should be easy to create a signature look, remarkably much of today’s street photography is fairly homogenous. We invite you to comment with your thoughts on the relationship between photographers, their cameras and the images they produce.